Message from Chancellor Richard L. Edwards:

November 18, 2016

Members of the Rutgers University–New Brunswick Community:

A year ago, I wrote to all of you announcing that the university would embark on an exploration of its early history, specifically examining to what extent our early trustees and benefactors were involved in slavery, how Rutgers came to inhabit land that once belonged to local Native American tribes, and how our institution may have benefited from these realities. To achieve a fuller understanding of this aspect of our early history, I created the Committee on Enslaved and Disenfranchised Populations in Rutgers History, which has been chaired by Board of Governors Distinguished Professor of History Deborah Gray White and composed of faculty, students, and staff.

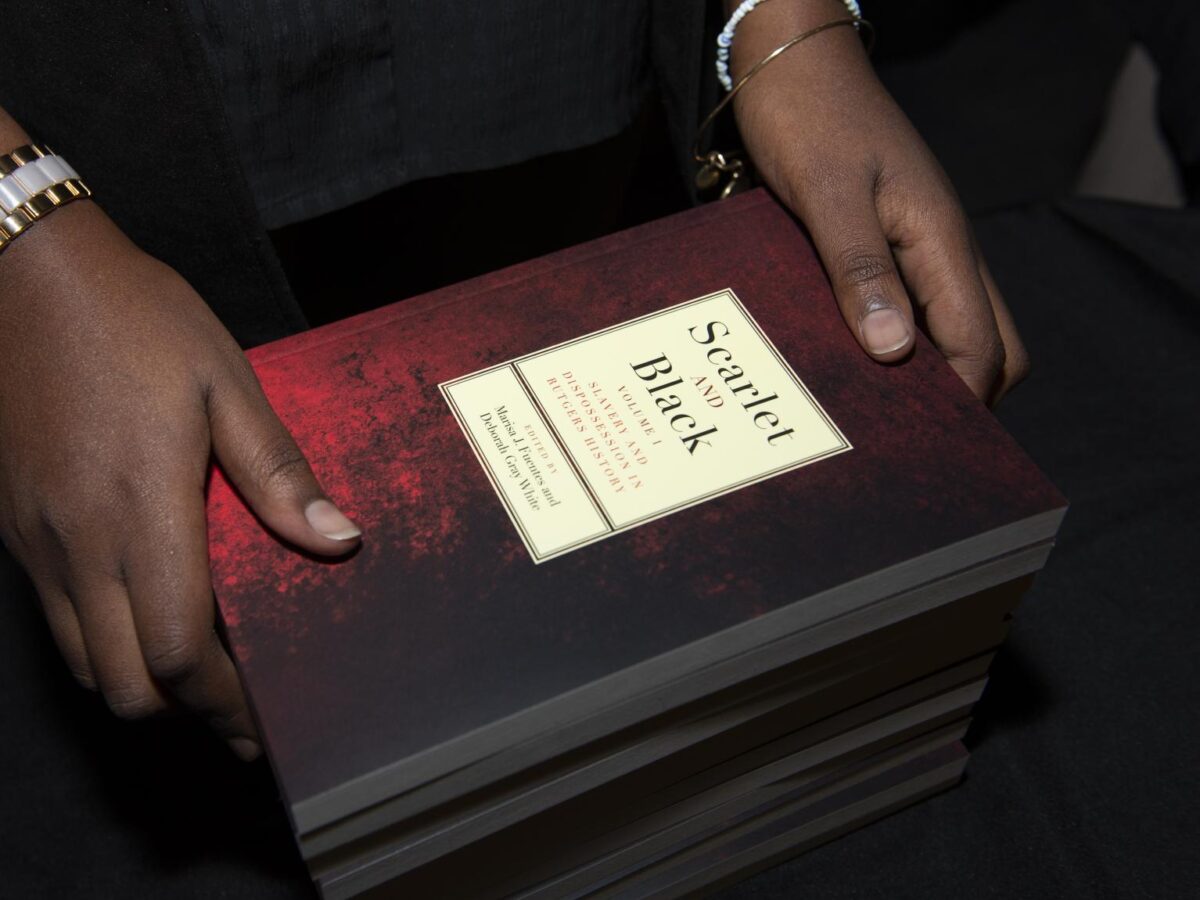

This afternoon, Professor White and her committee made their findings public. Their report is contained in the book Scarlet and Black, Volume 1: Slavery and Dispossession in Rutgers History, which has been published by the Rutgers University Press. The book reveals an untold history of those lost in the pages of our history and brings to the fore the fact that some of the institution’s founders were slave owners, and illuminates the displacement of the Native Americans who once occupied college land. Their major findings include:

- The discovery of Will, a slave who helped lay the foundation of Old Queens. Student researchers meticulously transcribed the documents they found, including a receipt book for the building of Old Queens, which now houses my office, the president’s office, and other administrative departments. In one of its first few pages, the receipt book reveals payments to local New Brunswick doctor Jacob Dunham “for the labor of his negro.’’ The slave’s identity would have been likely lost to history if Dunham had not kept detailed records of people who owed him money, which were preserved in the Rutgers archives.

- The revelation that abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth and her parents were enslaved by the family of Rutgers’ first president Jacob Hardenbergh. Jacob’s father, Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh, a founding trustee of Queen’s College, owned Truth’s parents at the time of her birth.

- The story of the Lenni Lenape Indians who were mostly displaced from New Jersey decades before the university’s founding, as well as those few who still lived in Central Jersey at the time the school was created, and whose young people were sent to an Indian boarding school in Connecticut rather than being welcomed at Queen’s College. Scarlet and Black also explores how the university benefited from the Morrill Act of 1862—the federal program that funded schools for the study of agriculture and the mechanical arts through the sale of Indian land out west.

Many of the truths reported in this work are complicated and uncomfortable, and there will be much discussion about how the university moves forward with this new knowledge. The committee has made several recommendations to me on how to make the best use of this new history.

My goal from the beginning of this historical exploration was that we would know truly the university we love dearly. This record provides us with a fuller knowing of the truth, but it also magnifies the stark differences between who we were at our founding and who we are today.

Queen’s College in 1766 was a reflection of higher education in the Colonial era: a place for male students from wealthy families, affiliated with a religious denomination, and funded by those who could afford to donate—many of whom had the means because of a connection to slavery. Rutgers University in 2016 could not be much more different from its ancestor. Today we are an institution of innumerable, and embraced, differences—a place where race, socioeconomic status, political thought, and values converge. This convergence is our greatest strength and the result of the path we charted, and then followed, out of the Colonial era.

I offer my thanks to Professor White and the committee for their tireless efforts. Their work has brought us some painful facts and, in so doing, has helped us to know Rutgers better.

Richard L. Edwards, Ph.D.

Chancellor, Rutgers University–New Brunswick