Removal to Louisiana: The Van Wickle Slave Ring

Removal to Louisiana

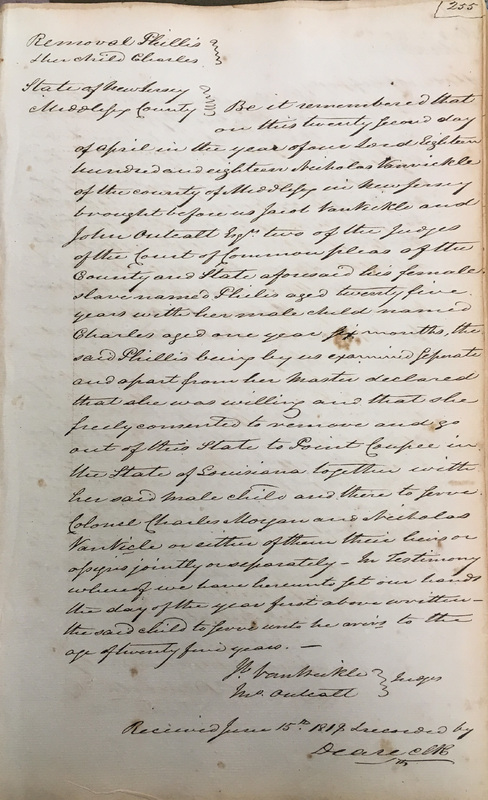

The Gradual Abolition Act made it more difficult for slave owners to profit off their slaves. Middlesex County Court Judge Jacob Van Wickle got around that ‘problem’ by running a slave ring where he would send slaves south to Louisiana to evade the law.[1] That allowed him to make a profit off slaves who would otherwise have to be freed once they reached twenty-five or twenty-one (Slaves could fetch $500 more in the South). Van Wickle would have his son Nicholas sell them down South to brother in law Charles Morgan, who would ‘buy’ the slaves in Louisiana. Slaves were sold south before reaching the age of emancipation, and in the case of Phillis (as seen at left), sometimes their newly born children were sold south with them, so Van Wickle could reap more of a profit. He sold over 50 slaves south through this process. As a judge, Jacob Van Wickle was crucial to the success of the scheme. Since an act of 1812 required two impartial justices to examine the slave before he could be removed and sent down South. By signing off on the removal documents that the slaves ‘voluntarily’ agreed to go south allowed him to skate around the law and profit off his slaves bodies to reap a profit (John Outcalt was the second Middlesex County judge who signed off on the removals with him).

Later, an 1818 law was passed “prohibiting their removal outside of New Jersey unless the master had lived there for five years and planned to do so permanently.”[2] Van Wickle had sent slaves south before the law was passed, in fact it appears that his actions led to outrage that led to the 1818 law being passed that restricted the sending of slaves south. It also appears that at least some of the slaves ages were falsified to have them be young enough to still legally be ‘slaves’ in New Jersey, so they could be then sold South. Some slaves appeared to be significantly younger than their ages; Phillis may have been one of them.[3]

The 1818 law was passed after there was a public outcry led by Quakers against the slave trade in the state. It banned individuals such as Charles Morgan from buying slaves and transporting them out of the state.[4] Charles Morgan was later indicted by a New Jersey jury of removing sixteen children and one adult, and Nicholas was indicted too. Yet Judge Jacob Van Wickle never was-and juries eventually acquitted all those accused.[5] Jacob Van Wickle covered his tracks by releasing ‘affidavits’ claiming that the slaves had gone South with perfect cheerfulness.[6] Slave removals drastically decreased after the law was passed, but that couldn’t reverse the hurt caused by the selling of slaves down south when they should have been freed. No one spent even a day in jail for the harm they had caused.

[1] Fuentes, Marisa, White, Deborah Grey, Scarlet and Black: Slavery and Dispossession in Rutgers History,(New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2016), 104.

[2] Geneva Smith, “Legislating Slavery in New Jersey,” Princeton University, https://slavery.princeton.edu/stories/legislating-slavery-in-new-jersey

[3] Jarret M. Drake, "Off the Record," NJS: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Summer 2015, 116; “An Abominable Business,” Old Bridge Village Heritage Center, http://purehistory.org/wp-content/uploads/Van-Wickle-Presentation.pdf?lbisphpreq=1

[4] James J. Giantino II, “Trading In Jersey Souls,” Pennsylvania History, Vol 77, no.3, 2010, 289-290, 292.

[5] Jarret M. Drake, “Off the Record,” NJS: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Summer 2015, 105.

[6] Drake, “Off the Record,” 119.